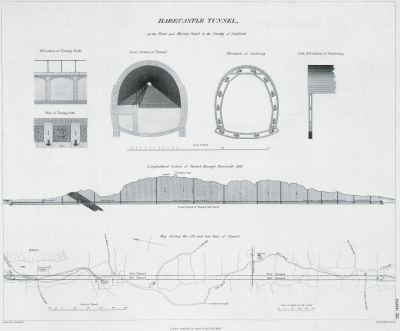

A new essay notes that the earliest theory of evolution first emerged from the Harecastle Tunnel in 1767, at the northern-most end of the Stoke valley…

“Erasmus Darwin started to think about evolutionary ideas when his curiosity was aroused by the discovery of mammoth bones at Harecastle near Kidsgrove”

I’m not sure where the author of this new essay got “mammoth” from, as that species is not specified in any source I can find. But certainly large fossil bones, including a giant fish, were found on the south side of the tunnel. According to Wedgwood…

“at the depth of five yards from the surface … in a stratum of Gravel under a bed of Clay of a very considerable thickness,”

Given that the surface has been quite cut back and down at Harecastle, by standing on the iron canal bridge there I guess one might be at the same level as a strata “five yards from the [original] surface”? The British Museum lists a giant shark-tooth from Harecastle, perhaps indicating the nature of the fish bones.

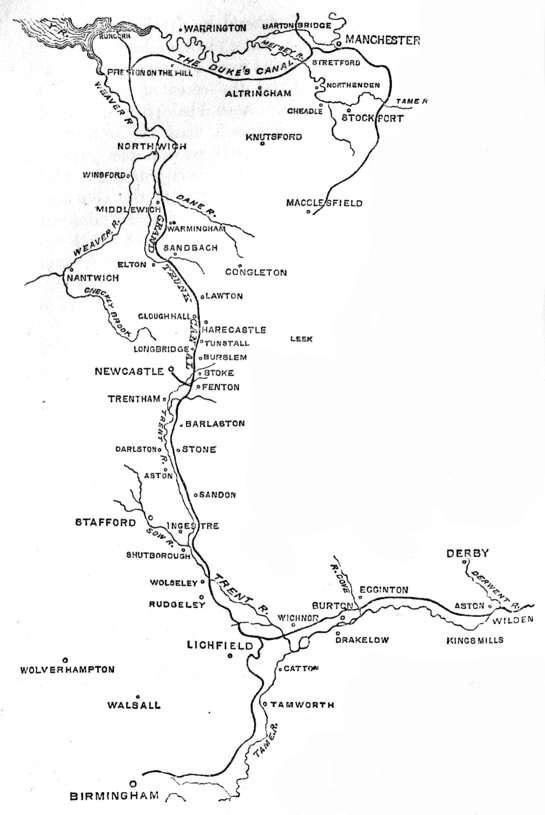

Apparently the obvious choice of the River Weaver for transport of the fossils to Darwin but not possible because, in Wedgwood’s words, on the Weaver… “the boatmen are sure to pilfer them”. Would that method have involved a packhorse to the Weaver at Crewe and then by sea from Liverpool to London and road to Lichfield? Anyway, by whatever means of transport they were sent, the “big bag” of bones arrived in Darwin’s stable-yard in Lichfield.

Darwin was a leading medical doctor of the time, but even he was rather baffled by the bag’s contents. He tentatively suggested, in a letter to Wedgwood, the likeness of a huge vertebrae bone to that of a camel. He also noted that what appeared to be a horn was more gigantic than any other horn he had heard of.

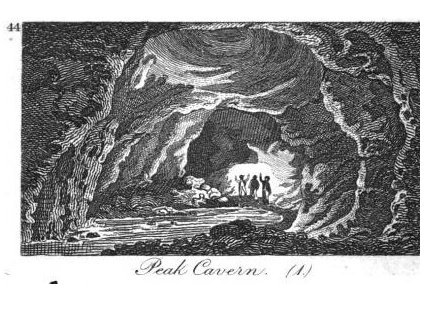

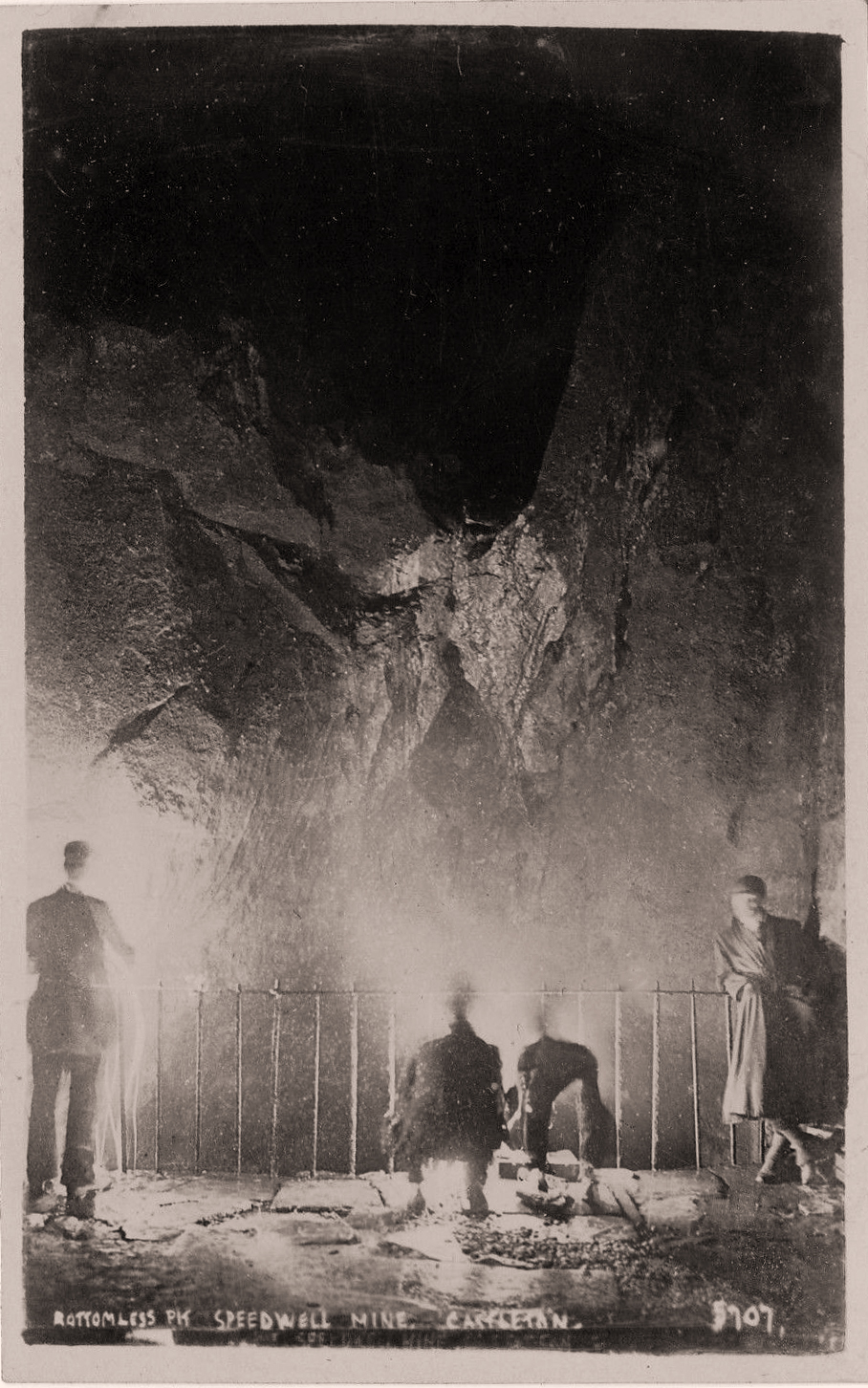

His curiosity piqued, and his pride in diagnosis perhaps just a little deflated, Darwin immediately decided he needed to gain an in situ understanding of just how rock strata were formed and how they lay. Unable to get to Harecastle from Lichfield (Wedgwood’s letter stated the journey would involve considerable cost, at that time) he took a swift two-day trip around the caves and rock strata of the Peak District, more easily accessed from Lichfield. He was in the company of Mathew Boulton of Birmingham, the geologist John Whitehurst of Derby, and Darwin’s eldest son Charles went along as assistant to his father. The men also went deep underground at Treak Cliff Cavern, a mine since Ancient Roman times as a source for ‘Blue John’.

Boulton took up this rare, but quite cheap, stone for his affordable Blue-John vases made in Birmingham. One popular TV historian has suggested that crushed ‘Blue John’ also contributed to the mix for the attractive ‘Wedgwood blue’ look in pottery, but I can find no supporting evidence for this. Yet it seems that Wedgwood did supply Boulton with jasperware plaques for Blue-John columns meant to elegantly ‘set off’ his new Blue-John vases.

Darwin somewhat jokingly proposed erecting, over the site of the gigantic fossil bones, a gigantic statue to the canal builder…

“I am determined to have the Mountain of Hare-castle cut into a Colossal Statue, bestriding the Navigation [the canal], and an inscription in honour of The Wedgewood.”

Sadly the ‘Giganticus Wedgwoodia’ statue wasn’t to be, and instead we only got an incredibly dull municipal monument at Bignall Hill. But Darwin began a far more monumental work. From the Harecastle bones, and the Peak District visit, Darwin formed a theory of ‘common descent’ — that all life must have at one time originated with a common ancestor. Most probably a shell-dwelling creature. Implied in this idea is the assumption that life diversifies in its forms, branching off into wholly new species, and that there must be some underlying driver for this process. Most pleased with his new idea, he was sure enough of its value to promptly have…

“fossil shells on his newly minted family crest, along with the motto E conchis oninia (‘everything from shells’)”.

He displayed this crest on his coach, until obliged to remove it from public display by an offended local Canon at Lichfield Cathedral. The Canon attacked him in a rhyme…

O Doctor, change thy foolish motto,

Or keep it for some lady’s grotto.

Thereafter, not wishing to be ‘cancelled’ and be deserted by his Church-going medical patients (the threatening implication of the poem), Darwin had to be content with using the crest privately and as a book-plate. But he cunningly took the Canon’s unwitting advice and method and slipped his evolutionary theories into a fine book of poetry aimed at ladies, The Botanic Garden. When that book became a runaway best-seller, a copy in every intelligent “lady’s grotto”, he felt confident enough to elaborate his 25 years of pent up ideas in the science book Zoonomia (1794-96), which had a substantial chapter on biological evolution. The new essay linked above gives an outline of this book’s key ideas. Unfortunately for Darwin the book ran smack into an unexpected cloud of national and international politics, a cloud not cleared up until after the Battle of Waterloo. It would take his grandson Charles to fully develop and prove beyond doubt the radical idea of evolution, and then others such as Huxley would ably pilot it through the hostile establishment consensus and towards a general acceptance.

[…] source for ‘Blue John’ rock which the story title alludes to. The cave played a key role in the discovery of the principle of evolution by Erasmus […]