It occurs to me that Stoke-on-Trent can claim to have had a part in not one, but two seminal stories about the nature of Time. The first is the famous The Time Machine by H.G. Wells, the earliest version of which was largely written at Basford and later went on to introduce to the world the concept of a time-travel machine. The other, which I’ve only just remembered has a local connection, is the Borges story “The Garden of Forking Paths” (1941). This introduced to the world the idea of multiple branching ‘time-paths’, down which… “Time forks perpetually toward innumerable futures”.

Unlike The Time Machine, the famous Borges story actually takes place in North Staffordshire. Specifically the story is framed by the wartime summer of 1916 and substantially set in a large rural house which, according to an address given by the phone book is in “a suburb of Fenton” which is relatively near the centre of Stoke-on-Trent. But which the narrator reaches by alighting from his train at a fictitious and very rural halt called “Ashgrove”, and then walking through a lush countryside of “confused meadows”. It helps to know here that Stoke is a strange side-by-side intermingling of the industrial and the verdant, as Arnold Bennett and others have observed. We can know the story is set locally because the spy tells us that the spy’s superiors knew only that…

“we were in Staffordshire” […] The telephone book listed the name of the only person capable of transmitting the message; he lived in a suburb of Fenton, less than a half hour’s train ride away. The station was not far from my home […] I was going to the village of Ashgrove but I bought a ticket for a more distant station.”

So anyone local will know this means the German spy must live in the county town of Stafford. This location is logical for a spy, since it is quiet and yet central to the country and has excellent frequent train connections. He has the local phone book easily to hand, which also establishes that he lives there and is not simply a visitor. From Stafford station he takes a local train to “the village of Ashgrove” to reach “a suburb of Fenton”. Ashgrove has its own rural halt…

The train ran gently along, amid ash trees. It stopped, almost in the middle of the fields. No one announced the name of the station. “Ashgrove?” I asked a few lads on the platform. “Ashgrove,” they replied. I got off. A lamp enlightened the platform but the faces of the boys were in shadow. One questioned me, “Are you going to Dr. Stephen Albert’s house?” Without waiting for my answer, another said, “The house is a long way from here, but you won’t get lost if you take this road to the left and at every crossroads turn again to your left.” […] The road [from the station] descended and forked among the now confused meadows.”

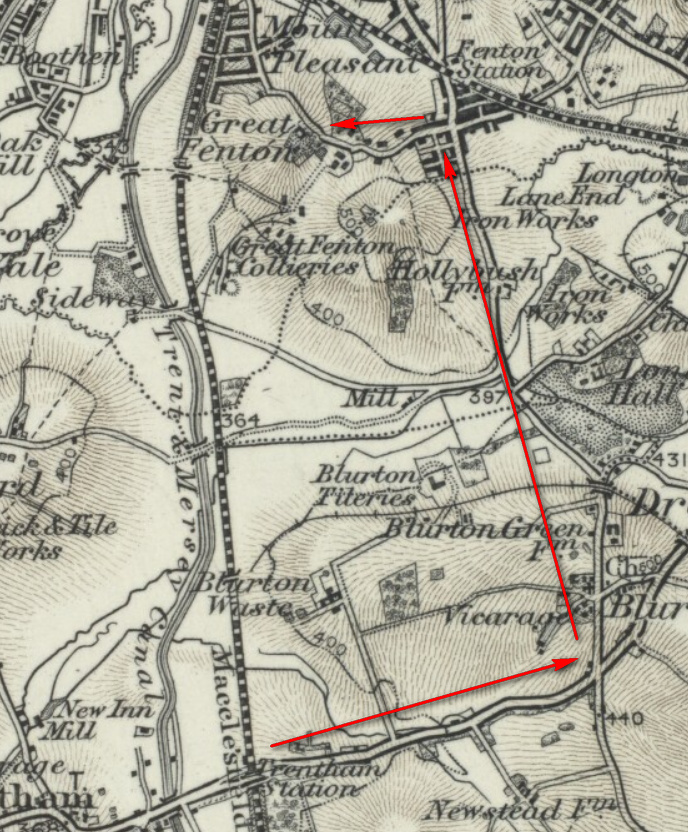

So this is again congruent with his living in Stafford. The spy is on the local stopping ‘milk-run’ train service from Stafford to Stoke-on-Trent, since he doesn’t change trains and some of the few passengers aboard are described as “farmers”. The isolation and terrain of the rural Ashgrove station can then only suggests the real-life halt at Trentham. Trentham serves as the green ‘grove’ for the industrial ‘ash’ city of Stoke, hence ‘Ashgrove’ is an apt coinage. The spy stands to face the road on exiting Trentham station, turns left and then turns left at every proper crossroads.

The spy could not have arrived there by travelling to the nearer Fenton train station, since that station was not on a train line to Stafford. Nor could he have gone on a little further to Stoke and then changed trains to go back toward Fenton, since i) he is being hunted, and time is of the essence and ii) he needs to avoid heavily policed and militarised places such as the mainline station at Stoke during wartime. He may also suspect that his pursuer will have phoned ahead from Stafford to Stoke. Thus he chooses the lonely rural halt of Trentham (the station near the famous Trentham Gardens), from where his map indicates he can walk unseen around the lanes to reach the “suburb of Fenton”. His pursuer, secure in the knowledge than any oriental man will be detained at Stoke, boards the next train and from the slide-down train window enquires at each platform (Stone, Barlaston, Trentham) if an oriental man had alighted there.

The spy thus arrives at Great Fenton, the “suburb of Fenton”, ahead of his pursuer. At that time Great Fenton had a cluster of several fine large houses…

“I arrived before a tall, rusty gate. Between the iron bars I made out a poplar grove…”

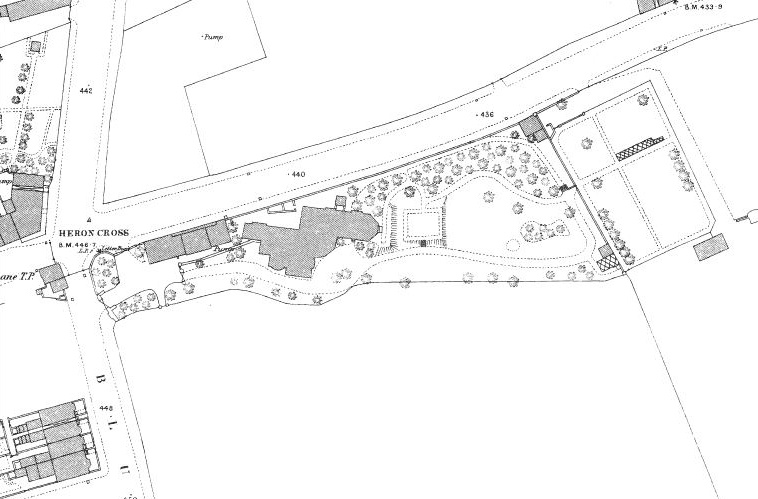

Great Fenton Hall had been demolished in 1900, so either Bank House, Great Fenton House or Heron Cottage are the obvious candidates for the house. Heron Cottage, though sitting on the crossroads rather than on a left turn off it, has the most interesting and relevant history…

At the south-east corner of the cross-roads at Great Fenton stood Heron Cottage, described in 1829 as a ‘small but superb edifice’ and c. 1840 as ‘agreeable for its seclusion’ and having ‘the character of an episcopal seat’ […] with Gothic features which included a cloister; Mason added a large redbrick dining-room and a ballroom.”

This seat of a local China plate manufacturer (seen above) has a historical link to armaments and ancient documents and dangerous murderous strangers, all elements found in “The Garden of Forking Paths”…

“August 1842 during the Chartists Riots, when it [Heron Cottage] was attacked in no uncertain terms. The rioters expected to find a large store of firearms as the large mansion was used as a depot for the Volunteers during the last war. Upon reaching the house, the mob smashed the windows and took possession of the house and plundered it, breaking all the furniture into pieces and throwing the beds through the upper windows onto the lawns below. There followed an attack on the wine cellar where its contents were quickly consumed and the larder cleared of its contents. Further damage was done when the mob set fire to ancient parchment documents relating to the history of the family. There were found on the premises only a couple of guns and a brace of pistols and a couple of swords.”

“… they plundered and almost gutted [Heron Cottage], stealing and destroying a vast amount of property. […] the whole country was in the utmost terror [of the mob, until dispersed by the military in Burslem]” (Gardener’s Chronicle, 1842)

In relation to this, note the spy’s vision of the many “invisible persons” surrounding the house, in “The Garden of Forking Paths”…

Once again I felt the swarming sensation of which I have spoken. It seemed to me that the humid garden that surrounded the house was infinitely saturated with invisible persons. Those persons were Albert and I, secret, busy and multiform in other dimensions of time.

Borges’s grandmother gives him a link to radical politics in north Staffordshire. She was the educated free-thinking Staffordshire girl Fanny Haslam, born and raised in north Staffordshire, specifically Hanley. She then moved to the British Argentine around 1870 in her 20s, where her father was an anarchist journalist. She was the one who taught Borges fluent English, and raised him in what was basically an English household. (A Companion to Jorge Luis Borges, page 11). Her grandfather had been one of those primitive Methodist preachers which North Staffordshire excelled in producing, and whose currents fed into various radical political sects later claimed by Marxists. This then gives Borges a family connection with north Staffordshire (Hanley is a stone’s throw from Fenton) and also to the Chartist riots associated with Heron Cottage.1

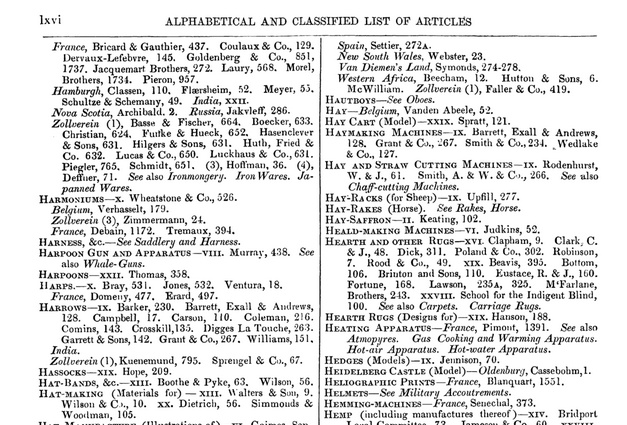

After the sacking and renovation, Heron Cottage became the home of Thomas Battam circa 1848-55. Battam was a fine painter of miniatures, Art Director at a local world-famous pottery, and the author of the “Guide to the Great Exhibition” (1851) at the Crystal Palace. This was a world-changing event, organised and promoted at the highest levels by Prince Albert. It was also a maze, of a kind, and a prism-like set of multiple turning points to the new future. Battam’s Guide to the Exhibition was a rather multifarious Borgesian catalogue of a sort…

It seems the sort of book likely to have been in Borges’s Anglo-Argentine father’s library.

The Staffordshire Advertiser, of 5th November 1864, called Battam on his death…

“a man of very refined and cultivated tastes […] sincerely respected by art circles in London”.

So far as I can tell Battam was not a Sinologist, as Stephen Albert is in “The Garden of Forking Paths”, but he was evidently a man of a similar nature and also concerned with china (of the pottery type).

It appears that Heron Cottage may have been standing in 1916. It stood just off the crossroads at Great Fenton in 1916, but Victoria County History states that… “The site was built over by the early 1920’s.”

Was Borges interested in the history of the Crystal Palace or its Great Exhibition, which may then have enticed him to write a story set at the home of its chief cataloguer? There is some evidence on that. In 1951 on the 100th anniversary of the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace he published an essay on ‘Coleridge’s Dream’. This mused on how a dream-like archetype of such a palace had been passed from Kublai Khan’s dream-inspired stately pleasure dome at Shang-tu in the 13th century, via Coleridge’s dream of it in 1797 (famously interrupted by the irritating “person from Porlock”). Borges thought of the idea of the “stately pleasure dome” as…

“Perhaps an archetype not yet revealed to men, an eternal object (to use Whitehead’s term) only gradually entering the world; its first manifestation was the palace; its second was the poem.”

Left unsaid in Borges’s essay, written on the 100th anniversary of the Crystal Palace, is that the Palace might — in Borges’ mind — have been the third such manifestation.2

Interestingly, H. G. Wells had this same Crystal Palace on his horizon for much of his childhood, and as such it must have been the inspiration for the distant Palace of Green Porcelain in The Time Machine. A fourth-such manifestation, Borges might have called it.

1. An amusing use was later made of this Staffordshire grandmother. In 1983 the Keele University medieval history lecturer Colin Richmond hoaxed the scholarly journal The Downside Review with his article “A Blatter of Rain and the Origins of Penkhull”. He…

“described how, in the steps of Edmund Bishop, he had followed the trail of the reliquary of St Penket (an obscure Anglo-Saxon virgin) from the cathedral of Fribourg in Switzerland to the Potteries and, eventually, to the garden of Jorge Luis Borges’ grandmother’s home at No. 21 The Villas (home of the then Head of Department at Keele) in Stoke-upon-Trent.”

2. In another related essay, “Coleridge’s Flower” (1945), Borges points out a passage in Coleridge which may seem to some to re-appear in Wells’s The Time Machine…

“If a man could pass through Paradise in a dream, and have a flower presented to him as a pledge that his soul had really been there, and if he found that flower in his hand when he awoke -Ay!- and what then?”

Borges concedes that, on Wells’s powerful use of this same motif in The Time Machine…

“Wells was probably not acquainted with Coleridge’s text” [but in Borges’s mind this does not matter, since for Borges…] This is the second version of Coleridge’s image. More incredible than a celestial flower or a dream flower is a future flower, the contradictory flower whose atoms, not yet assembled, now occupy other spaces.”

Dreams apart, Borges is likely correct on the matter of actual literary influence. The publication of the passage in Poetae: From the Unpublished Note-books of Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1895) was late in 1895 and thus could not have influenced The Time Machine. A review in the book-trade journal The Bookman of December 1895 shows that Poetae appeared for the Christmas market of 1895/96, and that it was made up of previously unpublished texts. The date of publication was thus around five or six months after the final book publication of Wells’s The Time Machine. I have also checked all of the earlier partial publications of fragments of the Notebooks. Clearly Wells’s motif of the flower originates in his fateful meeting in Etruria Woods in the spring of 1888, and not with Coleridge.

[…] A new scan of the famous story “The Garden Of Forking Paths” by Jorge Luis Borges in its 1958 English translation. The story appeared in The Michigan Quarterly Review, Spring 1958, and as I’ve shown is mostly set in Stoke-on-Trent. […]

This is great information on “The Garden of Forking Paths”. I am currently adapting it to a graphic novel, and I needed exact references to the locations and details. I can’t believe I found such a helpful link. Thank you.