This is my note on the historical accuracy of Chapter Two of the novel The Spyders of Burslem, set in 1869 in the town of Burslem in North Staffordshire:—

Burslem’s market was indeed on a Monday and not on a Friday. “St.” or ‘Pit’ Monday was the people’s unofficial extension of the weekend, and manufacturers and mine owners often found it difficult to get male workers to return to work on Mondays. Here is the book Fish and Chips, and the British Working Class, 1870-1940 on the topic…

The towns where this was so had a strong tradition of the observance of ‘St Monday’, especially among their mining populations: they included Bolton, Wigan, Burslem and Wolverhampton.

The Market Square is still proportioned as described, and slopes to the south.

The evening meal is indeed called “tea” in much of the West Midlands. Lunch is called “dinner”.

Sissy Mint was the name of a real Burslem chip-shop owner (male), although later in the 1920s. Denry’s didn’t exist in 1869.

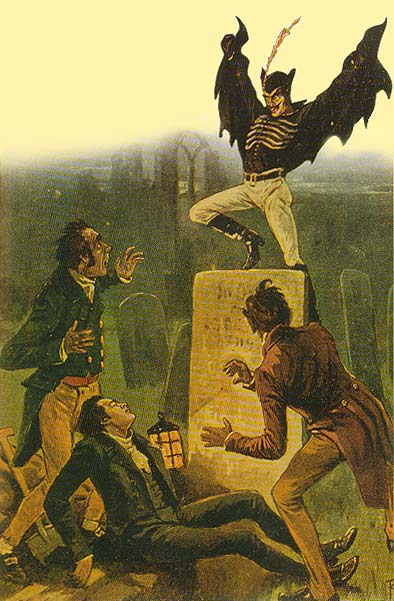

The local folk term “Spyder Jack” is an invention for the novel, but Jack was a common name in folklore, e.g. Jack-in-the-Green, and also later in popular culture. For example, the character of Spring Heeled Jack was born in the ‘penny dreadful‘ pulp publications in 1880.

Above: ‘Spring Heeled Jack’ illustration from the 1880s.

There are still very few trees in the town centre. Some trees have appeared under the regional development agency AWM’s regeneration schemes, but nature is still effectively “shut out” of most of the town centre, although it is certainly now creeping up the hill in the wasteland hillside behind The School of Art, which in a later chapter of the novel is imagined as the location of a “cliff” of squalid rookeries…

“The area was only partly paved, and with uneven cobbles, and I found no respectable streets in that part of the town. No robust and big-armed women had ‘stoned’ their front steps clean and gleaming with aid of brisk holystones, as they did elsewhere. It was the grimy and flaking quarter of the moonlight flitter, the cutpurse of quick hand, the blowsy fancy girl married to the lean drunkard for the hatching of a sniveling brood of children. I saw none of the plump and knowing cats that frequented the rest of the town. Ivy encroached on tall and crumbling houses, black snails copulated on stained walls, and old posters for gaudy entertainments peeled damply along the main thoroughfares. Its street people were few and furtive, mostly hurrying about their clandestine business all huddled down beneath caps and shawls.”

Above: the back way to Burslem today, imagined in the novel as the poorest part of the town centre.

The town’s many cats are an invention for the novel. They may have existed, since there would have been a need for rodent control. ‘Cheshire’ cats are a nod to Alice in Wonderland, but have some reality since the old British Blue breed does have a sort of natural smile to its face.

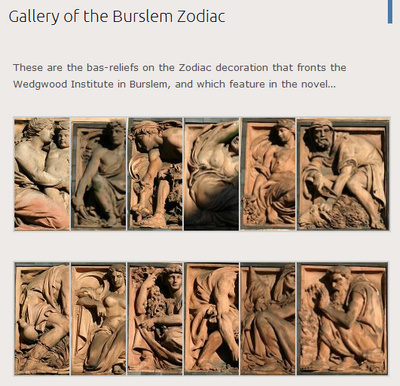

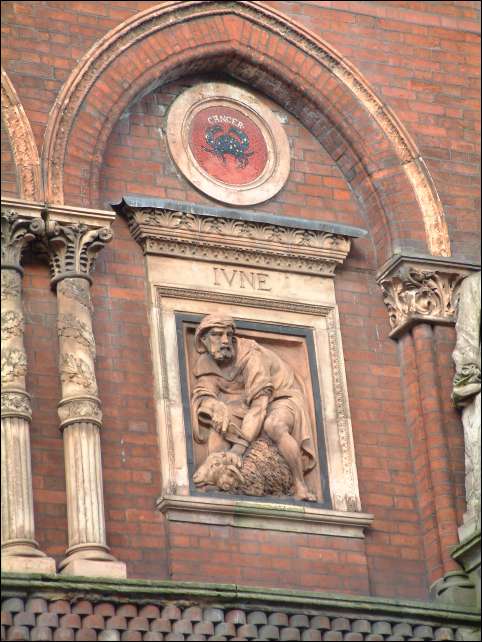

The Wedgwood Institute entrance interior is indeed heavily tiled with ceramics, as I remember it. The Institute building was the Burslem Public Library in recent years, and the public was admitted. But then the local Council closed it, and the building is now disused.

“Tile-wright” is accurate, as “wright” was once common as a master craftsman’s title. The name Torben is a nod to the chap who was involved in opened up and restoring the disused School of Art to be what it is today.

The physical description of Thomas Wedgwood is roughly accurate, had he lived to the age of ninety. His clothes are about right, if he was an intellectual gentleman of means who still dressed as if in an earlier period.

The details of the Midlands early photographers are all correct, including their activities and studios. Benjamin Stone really did go on a trip to photograph the children on Norway, Rejlander’s studio was on the Malden Road, etc.

Impressionism in painting was emerging at that time. But the Burlington Magazine was not established until 1903.

“The Tories pass their great Reform Act in the debating chamber of Parliament, an act by which urban working men would soon have the vote”

…this is correct, and refers to the Conservative Party’s 1867 Reform Act. Benjamin Disraeli was indeed prime minister, and was indeed Jewish. The Catholic emancipation was a real historical event, as was the famine in Ireland.

The “Potteries Benefit Building Society” is a truncation, for the purposes of dialogue, of the name “Staffordshire Potteries Economic Permanent Benefit Building Society”. This was a real society that was founded in October 1854.

The employment conditions are confirmed by memoirs and industry reports of the time. Women were employed as described.

The lack of prohibition of strong liquor was a fact of the time, as was alcoholism and fetal alcohol syndrome leading to deformed babies.

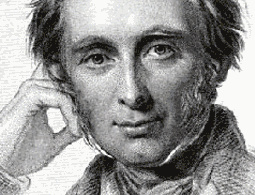

The idea that girls might be the best subjects for ‘initial’ education in a town was in the air at the time, through the writings and activities of Ruskin, and influential advocate for the education of girls. But even before that, education had by no means been limited only to boys in Burslem (see my book on the history of early Burslem and the Fowlea Valley). Ruskin appears in the novel in a later chapter.

Egerton was the name of a prominent local family who inter-married with the Wedgwoods. A “Temperance Society” has an anti-alcohol organisation, part of a huge anti-alcohol social movement of the time.

I’m not entirely sure if Charles Darwin was actually a cousin of Thomas Wedgwood. But Erasmus Darwin was certainly a friend of master potter Josiah Wedgwood and knew Thomas Wedgwood. The family is sometimes referred to in history books in terms of “the Darwin-Wedgwood family alliance” and there was much intermarriage.

Thomas Wedgwood did indeed have some correspondence links with the famous Lunar Society in his youth, but doesn’t seem to have ever attended a meeting.

The Wedgwood Institute was indeed funded by public subscription, not by the local state.

The Seven Dreamers pub is based on the well-known Leopard pub in Burslem. The reference in the changed name is to H.P. Lovecraft’s great un-written novel The Seven Dreamers.

“Potteries Atmospherical Loop Line Railway system”

…is an allusion to the real Loop Line railway, although the novel re-imagines it as being potentially powered by the aether. The real Potteries Loop Line was powered by steam and was completed as far as Burslem in 1873, when a station was opened. Thus, the hero’s Chapter One arrival at Burslem via Longport train station would have been historically correct for 1869.

The Burslem Literary and Scientific Society was a real group…

“The Burslem and Tunstall Literary and Scientific Society was founded for ‘all classes of society’ in 1838.” — The Victoria history of the county of Stafford.

… and it had leading female members such as Mary Brougham the printer, town librarian and bookseller. In the novel Mary Brougham appears in later chapters of Spyders. It seems that the Society did not last until 1869, though.

“Mr. Oakhanger” and “Mrs. Shuttershaw”. These names are borrowed from a memoir of a 1930s childhood in the Potteries.

The economics of food and trade, as briefly explained by Frederick Hoss the publican (now, who does that name remind you of…?), are accurate for the time.

Gas street lighting was indeed in the town at that time, and was a mature technology having been introduced in 1826.

The description of the view of the Burslem Town Hall, and the meat market behind it, is broadly accurate, but I have relocated the Meat Market a little to the north.