I happened to encounter the page on Holy Trinity Church, Hartshill, published by our local Council. Its description foregrounds an axe murder, of all things…

“Visit this magnificent church and listen to the gory tale of ‘Murder Most Foul’ – the story of an 1845 axe murder victim.”

Very cheerful. But perhaps it’s a relic from the Council’s immiserated socialist years, now in the past.

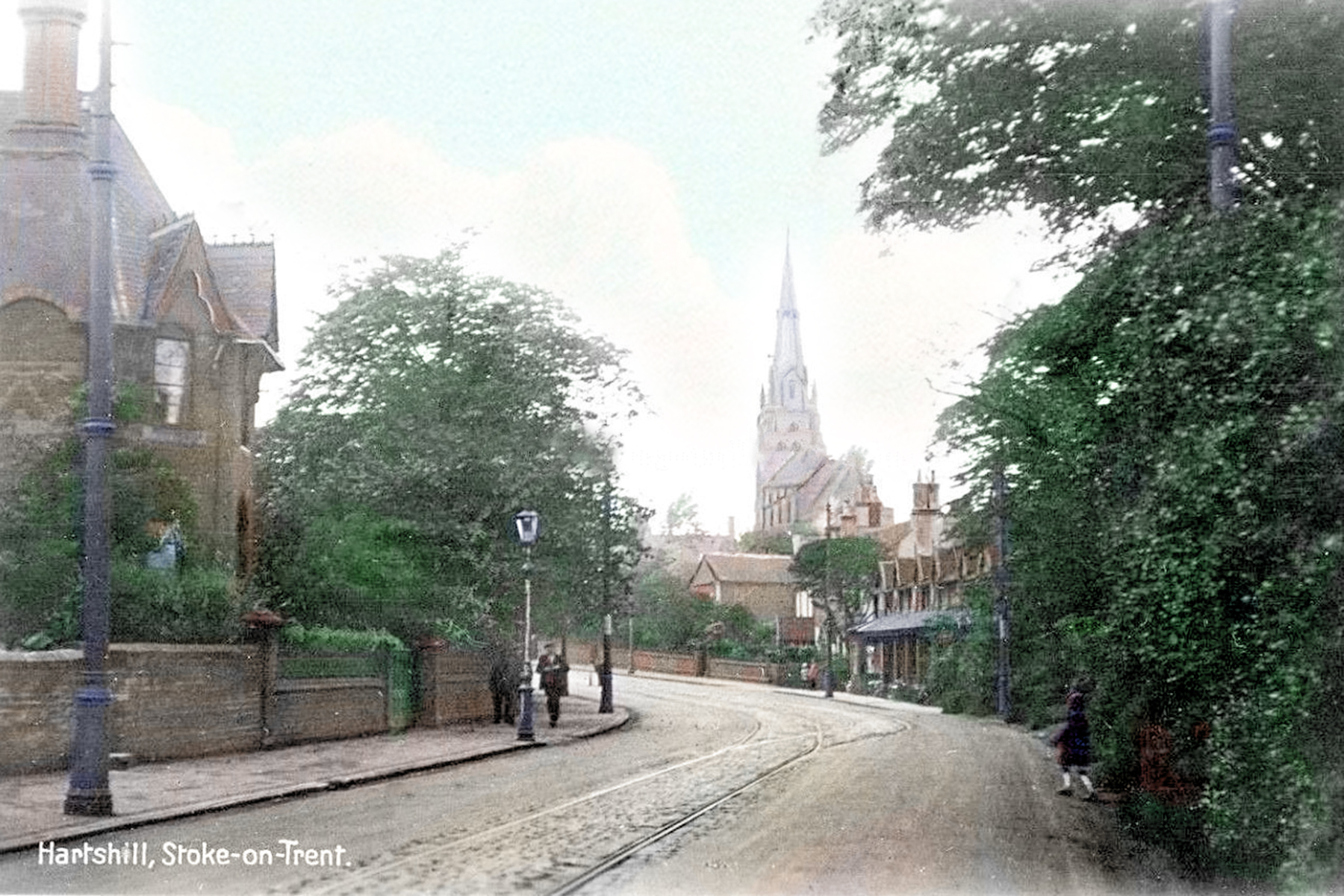

Here is Nikolaus Pevsner on the church, in his masterly survey Staffordshire (1974)…

“HOLY TRINITY, Hartshill Road. Built at the expense of Herbert Minton to the design of George Gilbert Scott in 1842, i.e. an early work. And, thanks to Minton’s attitude, also a large work. It is entirely Camdenian, or rather Puginian, i.e. it appears with the claim to be genuine Middle Pointed. w steeple, windows with geometrical tracery. The chancel incidentally was given its apsidal end only about the 1860s or 1870s. The date of the plaster ribvault is not recorded. It obviously cannot be Scott’s. It need hardly be said that glazed Minton tiles are copiously used inside, especially for the dado zone. Scott also did the SCHOOL behind and the PARSONAGE to the west, and again Herbert Minton paid. The school is quite large and an interesting design. The parsonage has been totally altered. Again built with Minton money is the long and varied group of Gothic brick houses with black brick diapering more or less opposite the church. They must be of before 1858.”

The Ecclesiastical Gazette of 1843 noted approvingly that…

“The form and arrangement of Hartshill church are those of the ancient English parish churches : a chancel of good proportions, a nave, aisles, south porch, and western tower, with spire.”

Historic England’s record page for the church adds a little more. Saying of the “apsidal end” that had been noted by Pevsner, that …

“The chancel was added in memory of Herbert by his nephew Minton Campbell. Notable pew ends carved by apprentices and stained glass windows depicting Biblical stories.”

The survey report Minton Tiles in the Churches of Staffordshire (2000) has a short summary account of the tiles of the interior. There was apparently a severe fire inside the church in 1872, which occasioned new work. There are also more details in the 1992 150th anniversary booklet. The fire means the tilework is mostly 1870s, apart from the nave pavements. Fish tiles added at that time, referencing the ancient Christian symbolism of the fish, were made by the Campbell Brick & Tile Co. I’ve discovered that this early symbolism must echo the original ethos of the original design work. For instance, The Ecclesiastical Gazette of 1843 noted the original chancel ceiling was… “divided by wooden moulding into panels, which are filled by tiles of a rich blue, studded with stars of gold, in imitation of the ceilings of some early churches.”

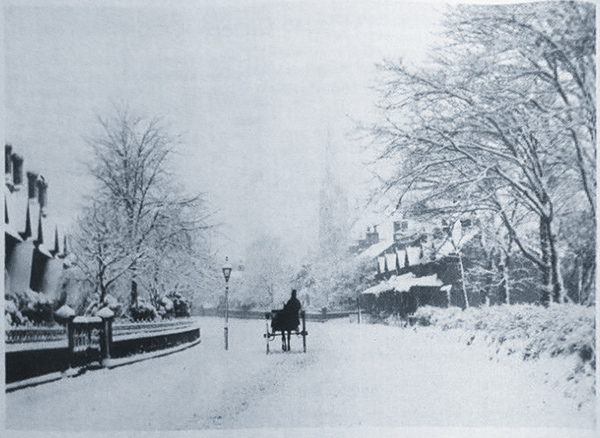

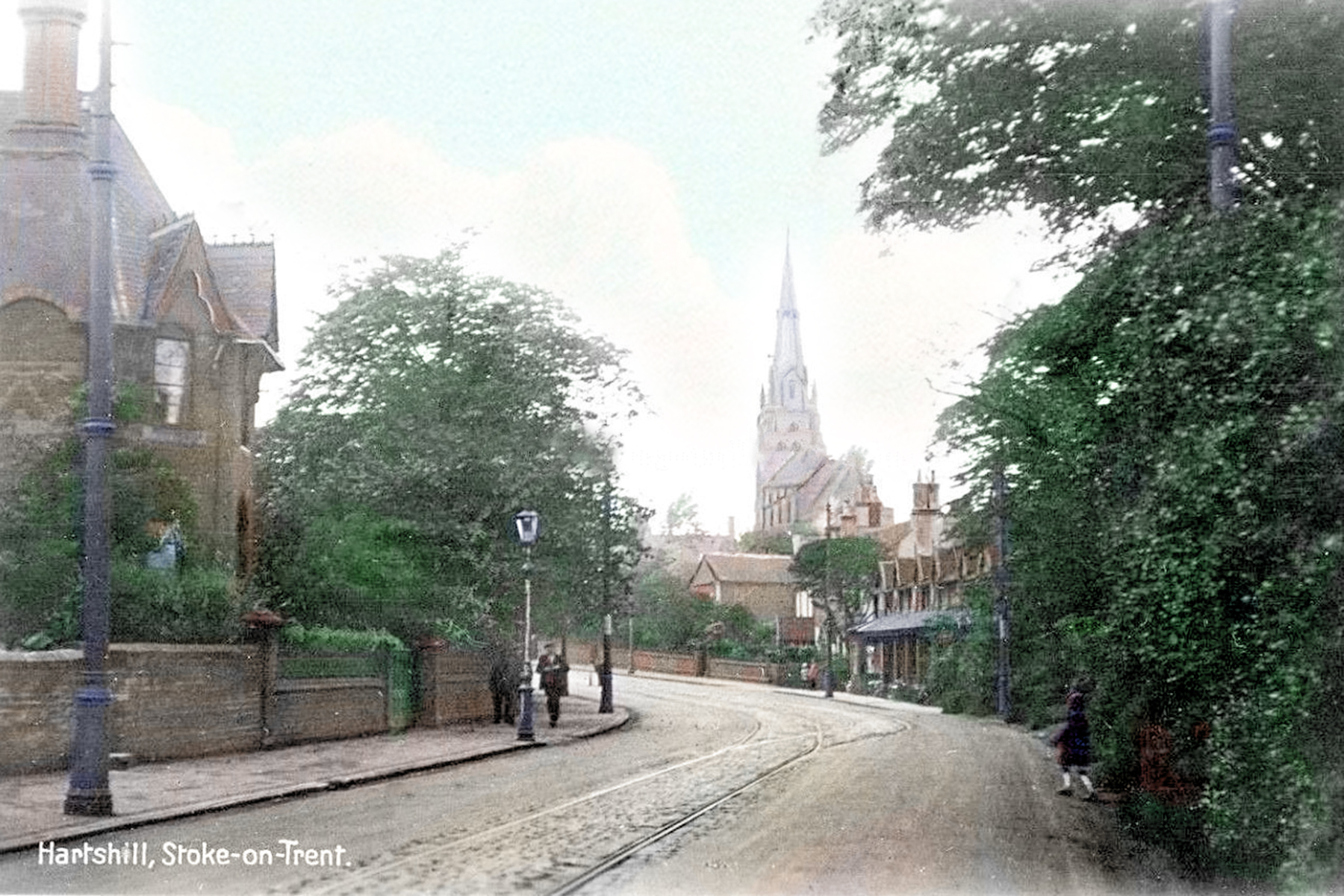

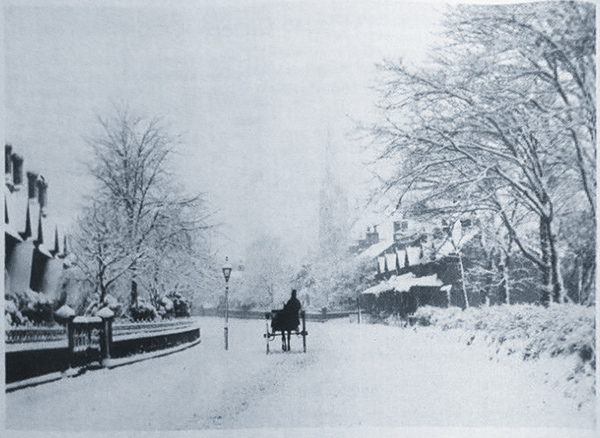

While undeniably plain when seen from the side at a distance (see above postcard), the book The Work of Sir Gilbert Scott (1980) suggests its fine interiors and windows were partly inspired by Lichfield Cathedral, and that these served to establish Scott’s reputation. These interiors, especially the “square-ended chancel” being…

“the first of Scott’s considered adequate by Victorian standards”

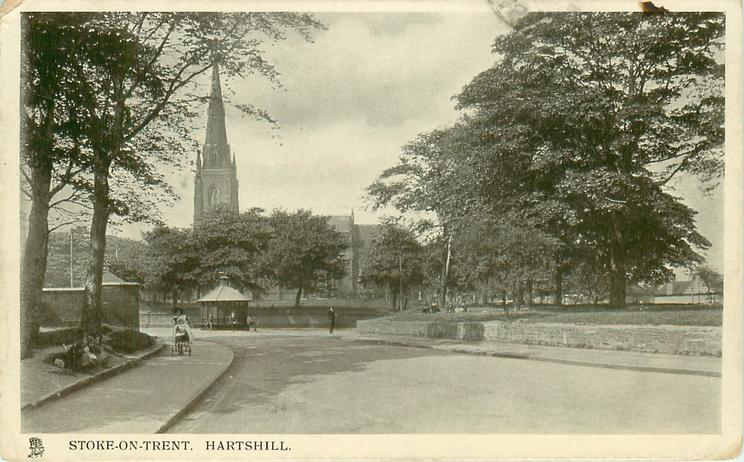

One can also see here (see above photos) how the exterior profile might have been designed to appeal more to those climbing up the road from Stoke in the valley below, rather than to those who saw the church side-on. Sadly Stoke-on-Trent Council (Lab) allowed the cottages on the right to be demolished. Labour allowed them to be replaced by a 1980s petrol station, delightfully flanked by a decrepit used-tyres dump. But the similar and larger buildings opposite have survived, and are still homes. Here these are seen from the opposite direction, with the church behind the camera and to the left…

The pub on the corner has also survived, and today is one of the best in Stoke.

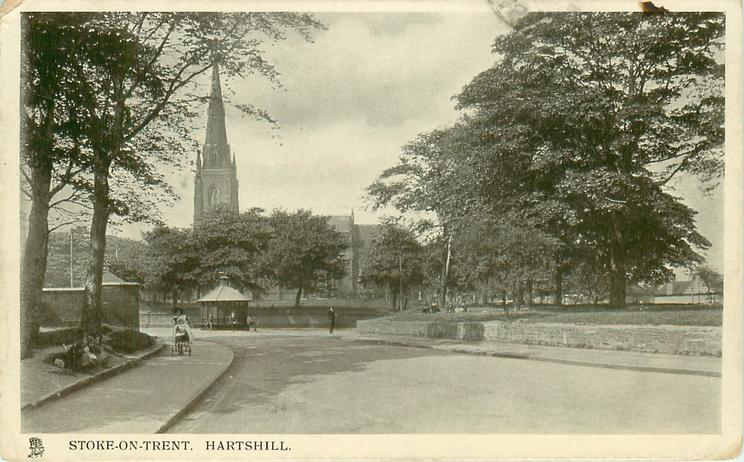

The Edwardians appear to have recognised the unappealing quality of the side-on view of the church, and they allowed trees to grow up to block it…

The potteries.org website cites Neville Malkin writing in the mid 1970s, on what was there before the church. This commanding crest of the hill was the site of a windmill.

“One of the few remaining windmills in the Potteries occupied this prominent site in Hartshill, until the late 1830s when it was demolished to make way for the church of the Holy Trinity”.

This is confirmed by Katherine Thomson‘s novel The Chevalier (1844), set in 1745. Thompson was a local writer who had grown up locally at Etruria…

“The Trent, narrow in this part of its course, where it has but lately quitted its source, wound through fertile fields, and beneath, at this point, a gentle rise, upon which, not many weeks since, wavy corn had been growing attracted the eye. A windmill stood on this fair bank, bearing the name of Harts-hill, just by a group of dark pines which rose against the blue sky.”

The Victoria County History has details such as the name of the Church’s first vicar, and details of its local mission houses in the Stoke valley below. It also adds just a little more detail on the size of the churchyard and who gave the churchyard land…

“The church of HOLY TRINITY at Hartshill was built and endowed in 1842 by Herbert Minton of Longfield Cottage (1792–1858). He also built the house for the incumbent to the west and the schools to the south and gave 2 acres of ground for the churchyard.”

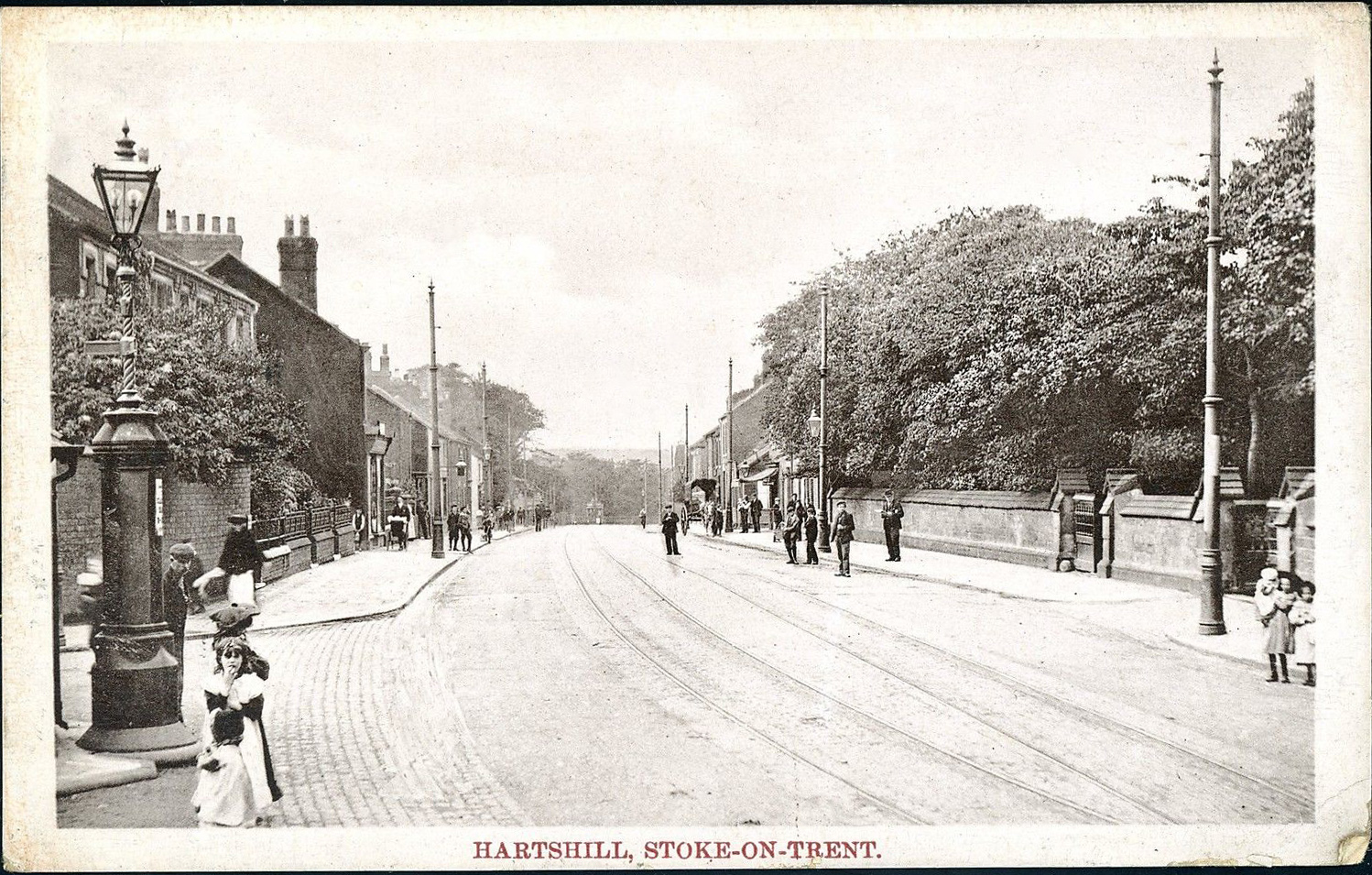

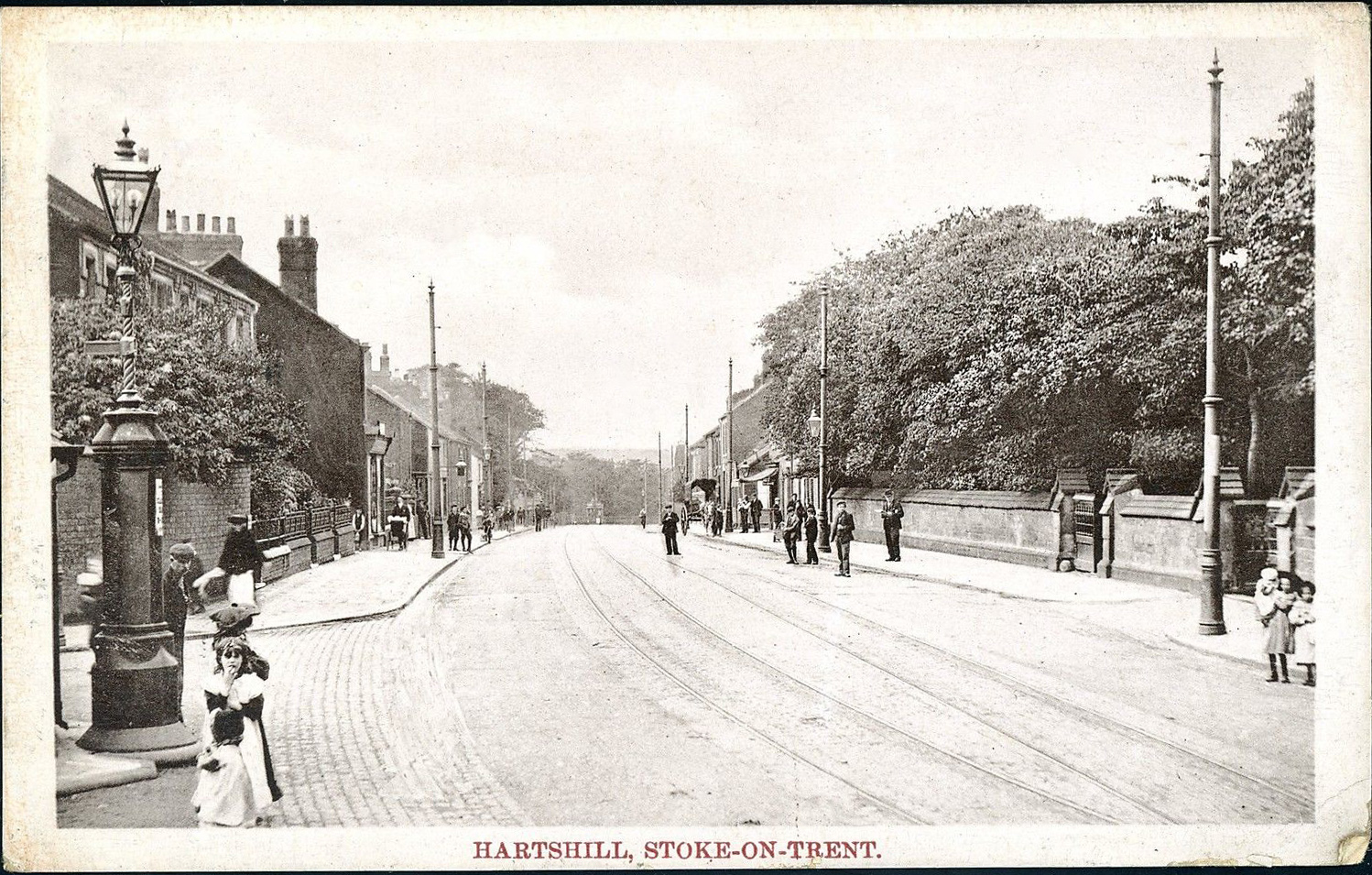

Here is a view of some of the local people Holy Trinity would have served in the 1900s. The main-road gates of both the church and the vicarage are seen on the right of the picture, and the camera looks toward Newcastle-under-Lyme. Tram-stops are just out of sight on either side of the camera.

Many of these lads would have later served in the First World War. In the 20th century the potteries.org website notes the church had a …

“new organ (1948) to serve as memorial to those who fell in the two World Wars.”

According to the National Archives the newer 1948 organ was overhauled and rebuilt in 1973.

The original organ was designed by Edward Wadsworth of Manchester, built by Bewsher and Fleetwood. According to The Architect and Building News it was destroyed in the fire of 1872…

“Hartshill Church, Stoke-upon-Trent. This church … damaged by fire, has been restored sufficiently to allow some of the services being resumed. Besides other damage, the organ gallery was burnt and the organ destroyed.”

Today the church still appears to have its bells, and with a fine peal, since I heard them being rung a few years ago while passing by. There are occasional open days, usually about one a year. There are apparently windows high in the tower: The Ecclesiastical Gazette of 1843 noted the new church’s spire that it was “pierced midway toward the apex by canopied windows”, though today the chances of being permitted to ascend and open a window on Stoke are likely to be slim.

WikiMedia has several modern photos including one interior.

What of the future, for such churches in Stoke? The government has just published a major review on the upkeep of such parish churches. It suggests two new networks of professionals: a temporary national staff working to boost suitable local uses of churches, while also helping local people to carry on such work at the grassroots; and a dedicated national network of ‘church repair professionals’ and apprentices, to ensure that churches don’t fall into disrepair or become fire-risks through lack of routine repairs and neglect.