I found a “face on a tree” in the Bradwell Woods, which are mentioned a couple of times in my new novel…

No Photoshop, other than the b&w conversion.

Surreal contribution to the recent Wilmslow Scarecrow Festival, in nearby Cheshire…

Photo: Steven Bullock

I was listening to the second of two BBC Radio 4 programmes on the history of philanthropy, when I was startled to hear something said by local Labour M.P. Tristram Hunt. He said of the Wedgwood Institute in Burslem…

“we’re standing in front of this beautiful elegant Wedgwood Institute, built from the gas industry and the ceramics industry and all the rest of it, and it’s meant to show their generousness, but you can also see — behind it — young men and women dying at 13 and savage inequality.”

Firstly I’ve always read that the Institute was funded by a wide public subscription, rather than being the result of the “generousness” of industry alone. The science classes and Library at the Institute in the 1870s were publicly funded, specifically by adding a penny on the local rates (i.e.: via a general local property tax) which meant they were being funded by a wide spread of local people. The books for the library were indeed donated — by John Ruskin, most famously, and he can hardly be called a slavering capitalist. I admit I haven’t ever seen the full listing of contributors to the Institute’s public subscription (has anyone?), and that the dilapidated old Brickhouse Works site was purchased by ceramics manufacturer James Macintyre for the building of the Institute. But it seems to me that — rather than the Institute being solely a monument to paternalistic largesse, as Hunt seems to imply — it was rather a generous gift from all of the town’s people. One meant as a living monument to the memory of Wedgwood, and open for the benefit of all.

Perhaps Hunt was thinking of William Woodall as a person who might justify his linkage. Woodall who was a key driving force behind the building of the Institute, being the Secretary of the Committee set up to fund and build it. But Woodall’s job as a young Burslem gasworks manager, and as a partner in the James Macintyre and Company china firm (later Moorcroft), hardly seems to be sufficient cause to damn the Wedgwood Institute as being somehow emblematic of child death and “savage inequality”.

Perhaps Hunt was thinking specifically of cobalt blue, used for the making of “Staffordshire Blue” ware at Macintyre & Co., in which Woodall was a partner. Hunt disparagingly mentions cobalt glazes earlier in the radio interview, so this seems a possibility. Cobalt could then contain up to ten percent arsenic, a known poison. At that time over 300,000 pounds of the ‘zaffre’ type of cobalt was imported annually to the UK, from Saxony and Prussia (now Germany/Poland). Although it was used in the glazes in a highly diluted form (1:150000), and the German industrial chemists were on the verge of developing ways to remove the arsenic.

Yet I can find no mention, in the historical record, of any deaths or health problems in the Potteries specifically attributed to the mixing or firing of cobalt glazes. Indeed, a modern article by Jeff Zamek, “A Problem With Cobalt?”, states that…

“A statistically accurate study of potters and their use of raw materials was sponsored at the 2000 NCECA [National Council on Education for the Ceramic Arts] meeting [and] a search of the National Library of Medicine data banks and other medical libraries did not reveal any diagnosed cases of potters contracting cobalt, manganese or arsenic poisoning.” [my emphasis]

Nor can I find, in any old book or government report, an instance of Macintyre & Co.’s Washington Works at Burslem being singled out as having notably bad working practices or health problems.

There certainly were health problems arising from some specific types of jobs in the wider Potteries: painters ingesting lead during painting, got from licking their brushes to get a point on them (many manufacturers responded by introducing leadless or reduced-lead glazes); scourers could inhale flint silicate dust, when polishing up the pots after kiln firing (responded to by manufacturers with forced ventilation, often inadequate); child labour had indeed been a general problem. There were around 4,500 child workers in the potteries at the 1861 Census, with many of the worst cases a result of a combination of alcoholic parents and small backstreet workshops. Some children would be sent to work by their inebriated parents “in the place of” the adult. But three Parliamentary commissions of inquiry, a strident and effective Victorian welfare movement, and a host of new laws were all regulating hours and conditions by the time the Wedgwood Institute was being planned and built in the 1860s.

Finally, what of Hunt’s claim for gas? This again points to his thinking of William Woodall, then a manager of the Burslem gasworks and also the Secretary of the Institute Committee. I suppose it’s possible that the Burslem and Tunstall Gas Company gave an especially large amount to the Institute’s public subscription? Perhaps it even installed gas lighting in the Institute for free? Even so, it does seem a little far-fetched to imply that Victorian gas lighting was therefore to blame for child deaths and “savage inequality”. Gas lighting was generally seen as a public good, by the 1860s. By that time domestic gas had also meant a huge reduction in the very unhealthy coal-smoke pollution. Gas street lighting, which all of Burslem had by the 1860s, meant the streets were safer at night, and on dark and icy mornings. Admittedly, mid-Victorian gasworks did not have a reputation as pleasant or healthy places to work — but the Gasworks Clauses Act of 1847 had long since been passed by Woodall’s time, and this strictly regulated the pollution from gasworks. Ground and air contamination outside of a gasworks grounds was apparently severely policed, especially in residential districts. We might also hope that the Burslem gasworks, apparently under the control of the progressive and enlightened William Woodall (schooled as a Congregationalist, a Chief Bailiff of Burslem, and later a Liberal M.P. and a tireless champion of women’s rights), was well run and had an eye on worker safety.

Readers of my novel The Spyders of Burslem may remember that there was a very casual passing mention of “clockwork typewriters”. In the novel these were spotted by the hero on a brief visit to the office of The Burslem Cosmograph newspaper. My thanks to Steve Sneyd, who has mentioned this “clockwork typewriter” notion to a typewriter collector contact of his in the United States. He had a lengthy reply on the topic, from which the following…

the only typewriter on the market at that time [1869] was the Mailing-Hansen “typing ball” which resembled clockwork, in that it was made of brass and had a mainspring and an escapement.

[If what was] meant by “clockwork” [was] that a typewriter was automatic, that was actually done. It was cumbersome and I don’t think it was widely used, but there was a device on the market — made by Hoover, I think, that generated punched paper tape, and this [tape] could then be used in an automatic typewriter to type the same letter as many times as needed.

Above: the Mailing-Hansen typewriter. Hansen’s first model was built in 1865, and many hundreds were sold.

The novel is of course, set in an “alternate” semi-steampunk 1869. The hero has only a very brief and flustered look inside the offices of The Burslem Cosmograph, and is anyway recounting past events from a distance of over 40 years afterwards. Which might account for his vaguely remembering the office’s typewriters as being of a generally “clockwork” design.

A revised and polished set of this blog’s historical notes have now been added to the paperback edition of The Spyders of Burslem.

My new free ebook, of nearly 100 pages: The Kidsgrove to Stoke Ridgeway: an elevated green route, to walk from Kidsgrove Station to Stoke Station (5Mb PDF). It photographs and describes a new ten-mile ridge walk, going all the way down the western edge of the Stoke-on-Trent valley. I’d estimate that about eight miles of the walk are either wooded, pasture, or parkland. Be warned, it has a delicious mix of strenous slopes — and is not for the faint-of-heart! Some parts of the route, such as the Bradwell Wood bit, are very muddy in winter and spring. It’s an unofficial continuation of The Gritstone Trail, a similarly tough “up and down” long-distance path which currently terminates at Kidsgrove.

Update: Nine years old now, at spring 2021. So walkers should expect that some aspects of the walk may have changed. Especially on the approach from the north to Wolstanton churchyard. I welcome update reports – please post in the comments below.

There’s a Wikipedia page for the Roman road that ran through North Staffordshire, the Rykeneld Street. Indeed, some it it probably still runs, under the earth, if anyone cared to dig for it properly and methodically.

An interesting sidelight on my portrayal of pneumatic speaking tubes in Burslem, in my novel The Spyders of Burslem. It seems such tubes were in use on the area, and over long distances, if only in the late 1600s. Around the year 1690 the Elers [redware potters] briefly settled in Bradwell Woods, near Burslem, to take advantage of the fine red clay there, and had…

“…a speaking-tube made of earthenware pipes, which they laid across the mile separating Dimsdale Hall and Bradwell Wood, and through which they conversed.” — “The Romance Of Old China: The Elers’ And Their Wares”, by Mrs. Willoughby Hodgson, circa 1910.

The earliest mention of this tube I can find via online methods is from The Athenaeum journal (1892). An account of a discovery of part of the tube was given in the book Staffordshire Pots and Potters (1906), which also gave an illustration of the tube sections found…

“The story was for many years received with amused tolerance as an old wife’s tale, more or less mythical, until accident revealed the actual existence of the pipes. […] William Wall, who afterwards became a builder, and was employed, during the year 1900, by a company of brewers to make certain alterations in a tavern called the “Bradwell House,” standing on the site of the Elerses’ pottery. […] during the excavations, in removing a wall, a number of pipes were found, together with a kind of cup, having no handle or bottom, evidently used for an ear or mouthpiece. […] They are at present exhibited in the Hanley Museum.”

A new article surveying the Peakland Spooklights…

“Strange lights in the sky hovering over rocky crags, dancing over wooded valleys, playing tag with each other, leading walkers astray.”

…in the Peak District and area.

Now available as an ebook for the Amazon Kindle ereader, the substantially expanded and revised second edition of my The Beauty of Trentham…

This special Kindle edition also contains additional historic texts describing the 19th century Trentham Park, Trentham Hall, and Trentham Gardens, not available in the paperback version.

As with all Kindle ebooks, a free sample of the first 10% of the book can be had on Amazon.

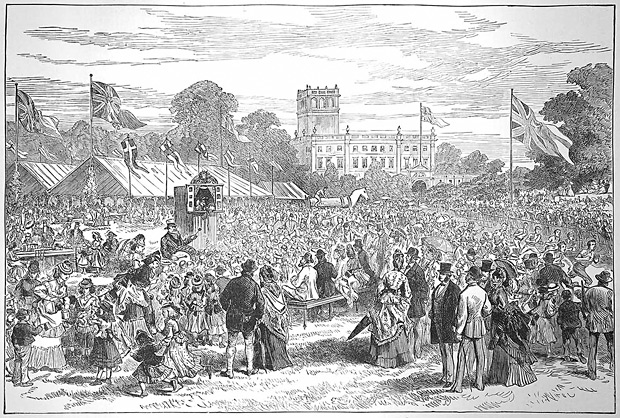

Painting Trentham Hall and Gardens, 1835-1935 runs until Sunday 8th July 2012 at the Newcastle-under-Lyme Museum and Art Gallery. This new exhibition of the art and illustration of Trentham Hall and Trentham Gardens includes some new works purchased recently at auction from Christies, by Henry Lark Pratt and the Minton factory. The rest seems to be drawn from the local museum archives. There’s a leaflet but no catalogue, so visit while you can. There are a few interesting items missing, such as the picture from 1872 which is seen below. Also missing are the major paintings by E. Adveno Brooke; Plot’s image of the first Trentham Hall in 1686 (although admittedly that’s before 1835); the watercolour map of the gardens and the hall elevation plan by Sir Charles Barry; the engravings of the Hall interiors in the 1880s; and the many photographic images of the Hall in ruins in the 1910s.

The exhibition’s information boards rather oddly give the distinct impression that Trentham was not open to the public, but it obviously was…

Above: Public fair at Trentham Gardens, 1872. Not included in the exhibition.

“The park and gardens are both open to the public; the latter on gala days, and the former at all times” — The History of the Tea-cup, 1878.

“A boon indeed to the densely-packed population that live in the Potteries such a park as that of Trentham must be, for the park is open to the public.” — Vanity Fair, 1882.

“All who have a shilling to spend have run away to spend it [at] a grand gathering of visitors at Trentham Park where all comers may freely enjoy themselves on the greensward. […] from eight in the morning until five in the afternoon, visitors poured in in a continuous stream; and at that hour the crowd in the park could not have numbered many less than forty thousand. Some of the young men engaged in cricket, prison bars, and other athletics games; but the majority preferred amusements in which the fair sex could participate; and many were the parties engaged heart and soul in the stirring polka, and other favorite dances. Picnic parties luxuriated beneath the shade of the noble trees skirting the park. Those who preferred “pairing off” wandered along the numerous glades opening out in different directions.” — report in Kidd’s Own Journal, 1853.

“North Staffordshire people have for so long enjoyed the privilege of walking in Trentham Park that it has come to be regarded as a public park” — North Staffordshire Journal of Field Studies, 1974.

“… on no green spot in England have more kissing rings been formed than in Trentham Park. If they could all have been marked, as the rings were marked where the fairies used to dance… ” — memories of the old potter Charles Shaw, who does not appear to be talking about making of the traditional Christmas Mistletoe ‘kissing ring’.

Interesting 2003 academic paper on the folklore of the mandrake plant, from Anthony John Carter of North Staffordshire Hospital. No other mention of Staffordshire in it, sadly. The paper’s free online.