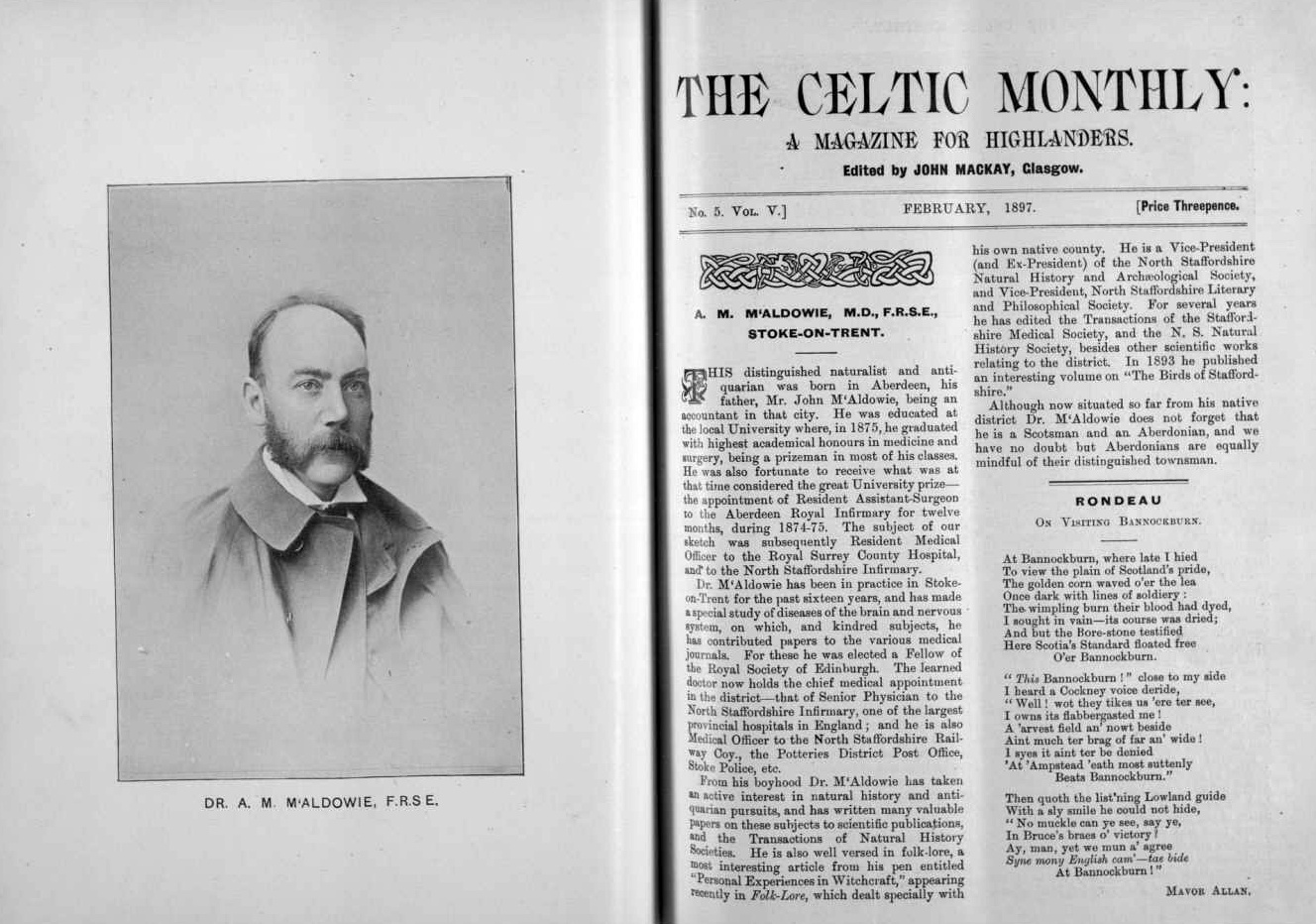

Alexander Morison McAldowie, from his article “Personal Experiences in Witchcraft”, Folk-lore journal, 1896…

“My first experience of witchcraft began at a very early age, before I was an hour old, in fact. My maternal grandmother, a pure-bred [Scottish] Highlander, held me close to the fire, and, taking care that she was unobserved, quietly fastened this witch-brooch beneath the ample skirts of my baby-garments. This form of brooch, fastened in the manner above described, was firmly believed to possess the power of driving the witches, which lay in wait for all newly born children, up the chimney. It protected the wearer from their malevolence, and brought good luck. The rite was practised universally in rural districts throughout the north in my grandmothers time. [His brother Robert had a small collection of witch-brooches] The two witch-brooches set in brilliants [i.e: set around with brilliant cut stones] [my brother] found in Staffordshire. One was the subject of a paper read before the North Staffordshire Field Naturalists’ Club in 1890 [Transactions, 1891]. It is interesting to note that the second specimen, which he obtained after the paper was read, is identical in every respect with “Shakespeare’s brooch,” found at Stratford-upon-Avon about seventy years ago.”

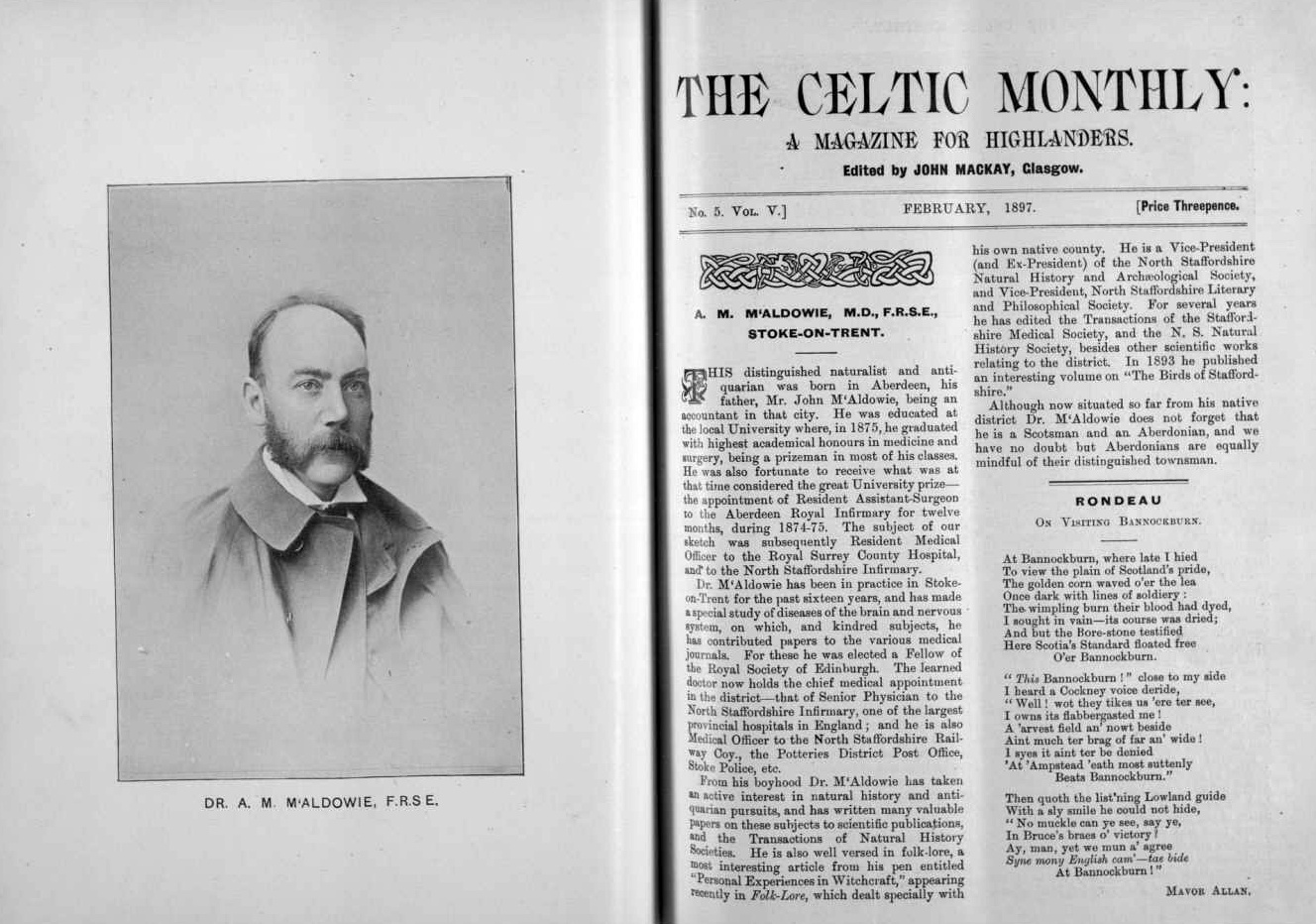

Alexander Morison McAldowie was the editor of Staffordshire Knots (1895), and Vice-President of the North Staffordshire Literary and Philosophical Society (c. 1897).

“Born in Aberdeen in 1852, Alexander Morison McAldowie moved to Staffordshire in 1876 when he was appointed House Physician at the North Staffordshire Infirmary. He later had a private practice at Brook Street, Stoke on Trent until his retirement in 1909. He then moved to Cheltenham, where he died in 1926. He was a member of the North Staffordshire Field Club from 1877 and was a keen amateur naturalist. He was also a Justice of the Peace for Stoke on Trent.” (from Staffs PastTack)

Here is his brother Robert McAldowie’s 1891 North Staffordshire Field Club Transactions article on the “witch brooch”…

NOTES ON A STAFFORDSHIRE WITCH BROOCH.

BY ROBERT McALDOWIE.

The small brooch which is the subject of this notice is heart-shaped, not of the conventional shape seen on a pack of cards, but is unequal sided, one side being full or rounded, the other indented. In size it is one inch wide and a little more than one inch in height. It is made of silver and set with eighteen crystals in what is called a fancy setting, that is, each crystal is set separately in a piece of silver, and then the pieces are soldered together in the required shape. This is the first example of this kind of setting I have met with, all the other heart-shaped brooches I have seen, set with stones, had a plain setting, just a band of silver with the stones set in it. The most peculiar thing about this brooch is its method of fastening. The pin is hinged on the back, comes through the open loop in the centre, and then the point rests on the front, so that no catch is necessary. This is a particularly safe fastening, for once the brooch is fastened on a piece of cloth it will not become undone unless the fingers are used, and this was a very necessary requirement for this kind of brooch. It was not an ordinary piece of ornamental jewellery, nor was it always used in what we, now a-days, would consider a useful manner; yet in the age in which it was worn it was a very essential article to the peace of mind of a certain class of people—namely the superstitious, who believed in witches and in luck. From the peculiarities I have described I have no doubt this is an example of what is known as a “Witch Brooch.” They were usually bought along with the wedding ring, and were supposed to keep away witches and bring good luck to the wearers. The lady wore it first but not exposed to view; then it was transferred to her children by a trustworthy nurse, who put it on their little garments while sitting by the side of the fire-place, so that if a witch had got a hold of the child, that evil being would find a ready mode of exit up the chimney, unable to withstand the influence of this miraculous charm.

The wearing of this brooch was thought to be an infallible safeguard against all kinds of evil, and it was considered a very foolhardy thing if parents neglected to put one of some kind on their children’s garments. I have examples of home-made brooches of such common materials as brass and mother-of-pearl, which I found in Scotland, the people who made them being, very probably, too poor to buy silver ones, but determined to have a “heart” of some description to keep their children from being witched.”

[A section on the fading away on the tradition in Scotland, which was within living memory at 1891, followed by a section on the “Shakespeare brooch”]

One of the brooches I have here to-night has this word [“love”] engraved on the back of it, and I have seen them with a scripture text, usually there are the initials of some persons. This Staffordshire one has no inscription of any kind. I got it in Lichfield, in a jewellers, who had bought two of them from an old servant of a family once living near the town; the other brooch he could not find, he thought it had been melted down for old silver, sharing the same fate as many others of the kind. I have inquired at many jewellers in North Staffordshire for these brooches, several remember seeing them but long ago, others have had them and consigned them to the melting pot as useless, of no interest, and not worth keeping. I should be very pleased if these few notes should help to preserve, or bring to light in this neighbourhood, some of these quaint and interesting old brooches.

As his brother states in his article “Personal Experiences in Witchcraft”, Folk-lore journal, 1896, Robert later found another witch brooch from Staffordshire some years after this paper was published.